Fallen Eagles

This page is dedicated to honoring the memories of our classmates who have passed away.

If you know of a classmate who has passed who is not listed here, you can add a new memorial with a photo by clicking the Add Memorial button.

You can also write a tribute or leave your comments about those already listed on the page.

Allen Keene

Birth Date:

1946-04-14

Graduation year:

1964

Deceased Date:

2024-02-27

Obituary:

Al's obituary

On February 27th 2024, Charles Allen, ‘Al’ Keene, walked up to the 18th green of his life journey, tapped in for birdie, and passed away surrounded by his family in Kennewick WA at 77 years old following a brave fight with brain cancer.

Allen was born on April 14th, 1946 to Charles and Dorothy Keene of Seattle, Washington. He was the middle of three siblings, older sister Linda Keene and younger brother Robert ‘Skeeter’ Keene.

The Keene’s lived in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Seattle, where Allen would attend Cleveland High School, where he played baseball and excelled with the golf team. After graduating from Cleveland High School in the spring of 1964, Al would attend Olympic College in Bremerton WA.

In 1966, during the height of the Vietnam war, Allen would have his number called in the draft, upon which he enlisted in the United States Air Force in May of 1966, where Allen served as an Aircraft Mechanic.

Allen Keene was honorably discharged in March of 1970 with the rank of Airman 1st Class, and would settle in the state of Virginia for a short time before returning home to Seattle in 1975.

Following his time in the Air Force, Allen would embark on what would be a lifelong career in sales. He had a unique talent of relationship building that made him very successful, and his career spanned multiple industries. Allen had the ability to understand the heartbeat of the customer. He loved what he did so much, he worked right up until his cancer diagnosis. He often bragged “It’s not work when you’ve known your customers for 25 years and call them your friends.”

In 1978, Allen met Sally Jo Noble, in Seattle. After dating for a time, they would be married that year in Lake Tahoe Nevada. Allen and Sally went on to have three sons – Sean Riley, Ryan Charles, and Brady James. They celebrated their 45th wedding anniversary in September of 2023. Al and Sally also have numerous grandchildren.

Allen was an avid golfer and drag racing fan. As a young man he was well known in the Seattle drag racing community, and would often regale friends and family with wildly embellished and humorous stories of racing his mom’s Chevy Nova.

He would play golf his entire life, passing on his love for the game to his sons. On a Sunday afternoon, he was either playing golf, watching golf or watching ‘the drags’ on TV. Allen loved spending time with his family, friends, and grandchildren above anything else. He and Sally’s house had a revolving door on the weekends of family and friends stopping in for visits.

He was a man well loved who had a life well lived, and leaves behind a great void that will take time to heal.

Allen is preceded in death by his parents, Charles Keene and Dorothy Keene (Baker). He is survived by his Sister Linda Maletta (Keene) of Desert Aire, Robert ‘Skeeter’ Keene of Ellensburg, his wife Sally Keene (Noble), his sons Sean Keene of Kennewick, Ryan Keene of Kennewick & Brady Keene of Richland, his grandchildren Carson, Charlie, and Emily of Kennewick, and Landon, Acacia, and Leila of Pasco.

Al’s wishes were that no service be held, and that his ashes be “buried in a sand trap”. This spring Allen’s ashes will be buried in the west greenside bunker on the 14th hole at Canyon Lakes Golf Course, where he had been a member with his sons.

In lieu of flowers, please make a donation in Allen’s name to the American Cancer Society.

Al's obituary

On February 27th 2024, Charles Allen, ‘Al’ Keene, walked up to the 18th green of his life journey, tapped in for birdie, and passed away surrounded by his family in Kennewick WA at 77 years old following a brave fight with brain cancer.

Allen was born on April 14th, 1946 to Charles and Dorothy Keene of Seattle, Washington. He was the middle of three siblings, older sister Linda Keene and younger brother Robert ‘Skeeter’ Keene.

The Keene’s lived in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Seattle, where Allen would attend Cleveland High School, where he played baseball and excelled with the golf team. After graduating from Cleveland High School in the spring of 1964, Al would attend Olympic College in Bremerton WA.

In 1966, during the height of the Vietnam war, Allen would have his number called in the draft, upon which he enlisted in the United States Air Force in May of 1966, where Allen served as an Aircraft Mechanic.

Allen Keene was honorably discharged in March of 1970 with the rank of Airman 1st Class, and would settle in the state of Virginia for a short time before returning home to Seattle in 1975.

Following his time in the Air Force, Allen would embark on what would be a lifelong career in sales. He had a unique talent of relationship building that made him very successful, and his career spanned multiple industries. Allen had the ability to understand the heartbeat of the customer. He loved what he did so much, he worked right up until his cancer diagnosis. He often bragged “It’s not work when you’ve known your customers for 25 years and call them your friends.”

In 1978, Allen met Sally Jo Noble, in Seattle. After dating for a time, they would be married that year in Lake Tahoe Nevada. Allen and Sally went on to have three sons – Sean Riley, Ryan Charles, and Brady James. They celebrated their 45th wedding anniversary in September of 2023. Al and Sally also have numerous grandchildren.

Allen was an avid golfer and drag racing fan. As a young man he was well known in the Seattle drag racing community, and would often regale friends and family with wildly embellished and humorous stories of racing his mom’s Chevy Nova.

He would play golf his entire life, passing on his love for the game to his sons. On a Sunday afternoon, he was either playing golf, watching golf or watching ‘the drags’ on TV. Allen loved spending time with his family, friends, and grandchildren above anything else. He and Sally’s house had a revolving door on the weekends of family and friends stopping in for visits.

He was a man well loved who had a life well lived, and leaves behind a great void that will take time to heal.

Allen is preceded in death by his parents, Charles Keene and Dorothy Keene (Baker). He is survived by his Sister Linda Maletta (Keene) of Desert Aire, Robert ‘Skeeter’ Keene of Ellensburg, his wife Sally Keene (Noble), his sons Sean Keene of Kennewick, Ryan Keene of Kennewick & Brady Keene of Richland, his grandchildren Carson, Charlie, and Emily of Kennewick, and Landon, Acacia, and Leila of Pasco.

Al’s wishes were that no service be held, and that his ashes be “buried in a sand trap”. This spring Allen’s ashes will be buried in the west greenside bunker on the 14th hole at Canyon Lakes Golf Course, where he had been a member with his sons.

In lieu of flowers, please make a donation in Allen’s name to the American Cancer Society.

There are currently no tributes.

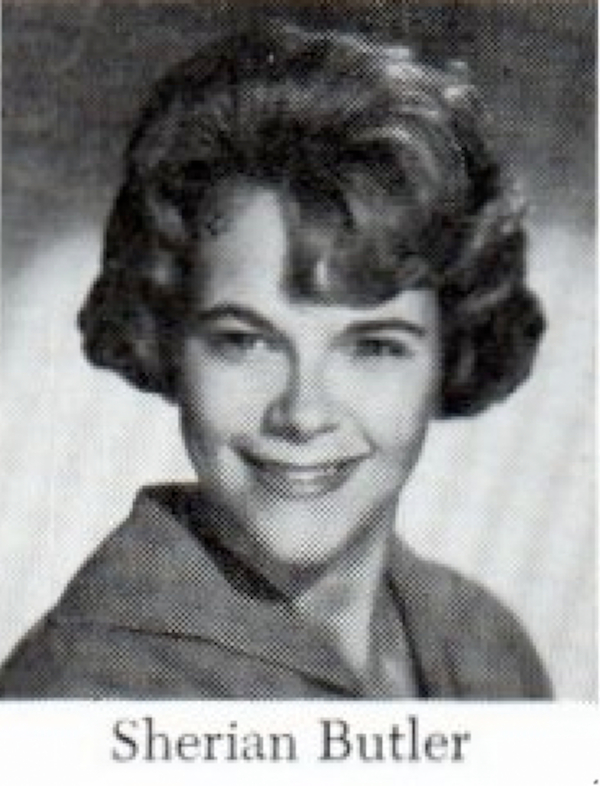

Sherian (Sheri) Grimes (Butler)

Birth Date:

1945-11-03

Deceased Date:

2024-01-30

Obituary:

On Sunday April 28th at

Rio Verde Estates

1402 22nd St. N. E.

Auburn, Washington

Time: 2p- 4p. at the Clubhouse

For any questions: Please call

Mike at: 206-947-1191 or

Barb at: 206-455-0940

On Sunday April 28th at

Rio Verde Estates

1402 22nd St. N. E.

Auburn, Washington

Time: 2p- 4p. at the Clubhouse

For any questions: Please call

Mike at: 206-947-1191 or

Barb at: 206-455-0940

There are currently no tributes.

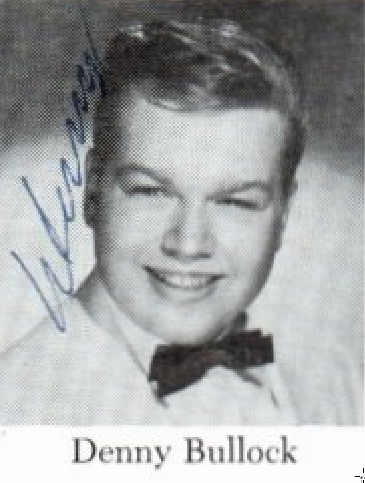

Dennis Bullock

Birth Date:

1946-07-24

Deceased Date:

2024-01-01

Obituary:

July 24, 1946 - January 10, 2024

Denny passed away on January 10,2024. He is survived by his wife of 25 years, Kathy Bullock; 3 daughters, Tracy (Phil) Montano, Dezi (Ed) Webler and Colleen Bullock and 4 grandchildren.

Denny was born July 24, 1946 to Horus and Lois Bullock. He graduated from Cleveland High School and the University of Puget Sound.

Denny entered the real estate profession in 1975. He was beloved by his agents as he became a Manager and General Manager over the years. He was an incredible mentor to many real estate agents throughout his career. Denny was an avid golfer. He always wanted his children to have great memories and they did. A celebration of life will be held at a later date.

July 24, 1946 - January 10, 2024

Denny passed away on January 10,2024. He is survived by his wife of 25 years, Kathy Bullock; 3 daughters, Tracy (Phil) Montano, Dezi (Ed) Webler and Colleen Bullock and 4 grandchildren.

Denny was born July 24, 1946 to Horus and Lois Bullock. He graduated from Cleveland High School and the University of Puget Sound.

Denny entered the real estate profession in 1975. He was beloved by his agents as he became a Manager and General Manager over the years. He was an incredible mentor to many real estate agents throughout his career. Denny was an avid golfer. He always wanted his children to have great memories and they did. A celebration of life will be held at a later date.

There are currently no tributes.

Roman Jurewicz

Birth Date:

1946-08-10

Graduation year:

64

Deceased Date:

2023-11-28

Obituary:

Roman Jurewicz, 77, of Flower Mound, TX passed away peacefully on Tuesday, November 28, 2023, surrounded by family.

Roman was a beloved son, brother, and uncle. He was born to Jan and Salomea Jurewicz on August 10, 1946 in Wetzlar D.P. Camp in Germany. His parents came to the United States with him and his brother, Bruno, in May of 1949 to Washington State and lived in Seattle. Roman graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. He was a member of the U.S. Marine Corps from 1964 to 1972, having served two active-duty tours in Vietnam.

After serving in the Marine Corps, Roman went to work driving taxi cabs in California, where later he drove 18-wheel trucks throughout the continental United States. He stopped driving in November of 2007 when he suffered a stroke and moved from California to Flower Mound, TX to live with his sister, Mary (Romaszewski) and her family. He rode his bicycle to various libraries around the metroplex to pick up and exchange audio books, mainly westerns and mysteries. Roman absolutely loved to watch old movies, westerns, and Perry Mason, the Duke University Men’s basketball team, especially when Mike Krzyzewski was their coach.

Roman is survived by his two brothers, Bruno, George and his wife, Vera, his sister Mary Romaszewski and her husband, Sylvester. He is also survived by several nephews and nieces from Seattle, Mexico, and Texas. Roman was preceded in death by his parents, brother Stephen (stillborn in Germany), and sister-in-law Rebecca. Roman will be greatly missed by his family and friends as he brought joy and a smile to anyone he spent time with.

Roman Jurewicz, 77, of Flower Mound, TX passed away peacefully on Tuesday, November 28, 2023, surrounded by family.

Roman was a beloved son, brother, and uncle. He was born to Jan and Salomea Jurewicz on August 10, 1946 in Wetzlar D.P. Camp in Germany. His parents came to the United States with him and his brother, Bruno, in May of 1949 to Washington State and lived in Seattle. Roman graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. He was a member of the U.S. Marine Corps from 1964 to 1972, having served two active-duty tours in Vietnam.

After serving in the Marine Corps, Roman went to work driving taxi cabs in California, where later he drove 18-wheel trucks throughout the continental United States. He stopped driving in November of 2007 when he suffered a stroke and moved from California to Flower Mound, TX to live with his sister, Mary (Romaszewski) and her family. He rode his bicycle to various libraries around the metroplex to pick up and exchange audio books, mainly westerns and mysteries. Roman absolutely loved to watch old movies, westerns, and Perry Mason, the Duke University Men’s basketball team, especially when Mike Krzyzewski was their coach.

Roman is survived by his two brothers, Bruno, George and his wife, Vera, his sister Mary Romaszewski and her husband, Sylvester. He is also survived by several nephews and nieces from Seattle, Mexico, and Texas. Roman was preceded in death by his parents, brother Stephen (stillborn in Germany), and sister-in-law Rebecca. Roman will be greatly missed by his family and friends as he brought joy and a smile to anyone he spent time with.

There are currently no tributes.

Robert (Bob) E Hedgcock

Birth Date:

1945-11-21

Deceased Date:

2023-07-03

Obituary:

Bob was born in Seattle, WA to Marshall and Elizabeth Hedgcock. He lived most of his life in Seattle. He passed after a long illness and is survived by his wife of 50 years, Joline Hedgcock (Studley) and was preceded in death by daughter, Jennifer Ann Hedgcock in 2005. Bob graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. Bob served in the Army in Vietnam from 1967-69. He worked in warehouses most of his life and was a member of the Teamsters Union. He was a long time member of Assumption Parish. Bob loved to read, play pinochle, and take road trips. His favorite holiday was the 4th of July, a kid at heart with the fireworks. Bob is survived by his 3 sisters; 6 nieces and nephews and 10 grand nieces and nephews. He will be missed by all who knew him.

A memorial mass will held on October 14, 2023 at 11 am at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, 7000 35th Ave SW. For further information please follow https://woodlawnfhcc.com

Bob was born in Seattle, WA to Marshall and Elizabeth Hedgcock. He lived most of his life in Seattle. He passed after a long illness and is survived by his wife of 50 years, Joline Hedgcock (Studley) and was preceded in death by daughter, Jennifer Ann Hedgcock in 2005. Bob graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. Bob served in the Army in Vietnam from 1967-69. He worked in warehouses most of his life and was a member of the Teamsters Union. He was a long time member of Assumption Parish. Bob loved to read, play pinochle, and take road trips. His favorite holiday was the 4th of July, a kid at heart with the fireworks. Bob is survived by his 3 sisters; 6 nieces and nephews and 10 grand nieces and nephews. He will be missed by all who knew him.

A memorial mass will held on October 14, 2023 at 11 am at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, 7000 35th Ave SW. For further information please follow https://woodlawnfhcc.com

There are currently no tributes.

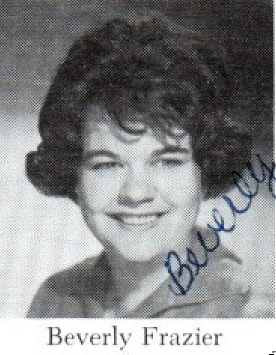

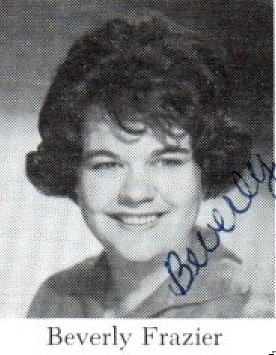

Beverly Durante (Frazier)

Deceased Date:

2023-05-20

Obituary:

Beverly Jeaneene Durante of Seattle, WA passed on May 20, 2023 at the age of 77. She is survived by 3 children and 5 grandchildren. A celebration of life will be held Sat., June 17, at Bethaday Community Learning Space, 605 SW 108th St., Seattle WA 98146, from 11:000 am -4:00 pm.

Beverly Jeaneene Durante of Seattle, WA passed on May 20, 2023 at the age of 77. She is survived by 3 children and 5 grandchildren. A celebration of life will be held Sat., June 17, at Bethaday Community Learning Space, 605 SW 108th St., Seattle WA 98146, from 11:000 am -4:00 pm.

There are currently no tributes.

Claudia June Allwine

Birth Date:

1945-11-17

Deceased Date:

2023-03-23

There are currently no tributes.

Mark Allison Wartes

Birth Date:

1945-09-19

Deceased Date:

2023-01-26

Obituary:

On Jan. 26, 2023, Mark Wartes passed away at the age of 77.

Born September 19, 1945, in Seattle, Washington, to Bill and Bonnie Wartes, Mark was a loving husband, father and grandfather. He and his best friend and wife, Denise (Cross) Wartes celebrated 50 years of marriage in 2022. He loved and doted on his children, grandchildren and family.

Mark grew up in Utqiagvik, where he maintained lifelong friends and family. He attended school in Utqiagvik, Alaska, Sequim, Washington, and Seattle, Washington, and college at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, North Carolina, where he was a member of the winning soccer team.

After his Air Force military service in Bitburg, Germany, he returned home to his beloved Arctic and lived at the Colville River Delta. While living in the Arctic, he maintained a subsistence lifestyle, worked with various oil companies, including helping build the first temporary oil drilling ice island, guided numerous researchers across the slope in the early days of building the trans-Alaska pipeline as they established baseline studies of various species, land and water formations. Mark and his wife Denise lived there several years before moving south to Fairbanks, where they continued to raise their children, Marwan Wartes and Marita (Wartes) Bunch.

In Fairbanks, Mark owned a commercial floor covering company, where he and his brother, Eldon, worked all across Alaska, eventually retiring to serve several years as the general manager of Water Wagon, a local family owned water delivery company.

As a private pilot and registered big game guide, Mark flew and hunted along the Arctic coast and the Brooks Range of Alaska. He then spent a number of summers as a fishing boat captain in Valdez in Prince William Sound.

He and his brother, Eldon, coached a number of youth soccer and hockey teams, along with playing hockey himself with the Fairbanks Old Timers hockey team for several years.

He was a proud and active member of the Fairbanks Presbyterian Church and Yukon Presbytery, serving as the Presbytery Native American liaison for many years, along with being involved with Bingle Memorial Camp.

He enjoyed dancing with his beloved Pavva Inupiaq Dance group, involving his wife and grandchildren in the group, and performing locally many times.

He is survived by his much loved wife, Denise (Cross) Wartes, son Marwan and wife Erin, daughter Marita and husband Matthew Bunch, beloved Aapa to grandchildren Gwendolyn, Owen, Blake, and Trevor Bunch, and Matia Wartes. He was so pleased that all of his siblings came to visit him recently: Merrily Lowry (Steve), Teena Helmericks (Jim), Marti Bennett (Richard), Clayton Wartes (Judy), and Eldon Wartes (Debbie). Also surviving are many nieces, nephews, cousins and friends.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made in memory of Mark Wartes to the University of Alaska Fairbanks in support of the Wartes Rural Alaska Honors Institute scholarship. Contributions may be made online at bit.ly/3wHPvqK . Checks can also be mailed to: UAF Development and Alumni Relations, PO Box 757530, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775. Please make checks payable to "UA Foundation" and include "In memory of Mark Wartes" in the memo. If you have questions, contact the UAF Development and Alumni Relations at (907) 474-2619.

Several members of his family are traveling to Utqiagvik to attend Kivgiq Feb. 2-5, 2023, to celebrate his beloved Arctic. A memorial service is being planned in Fairbanks on May 20, 2023, with final burial on the Arctic coast.

Funeral arrangements were entrusted to Fairbanks Funeral Home.

Condolences can be sent to the family at: denisewartes@yahoo.com, or 1713 Central Ave., Fairbanks, AK 99709.

On Jan. 26, 2023, Mark Wartes passed away at the age of 77.

Born September 19, 1945, in Seattle, Washington, to Bill and Bonnie Wartes, Mark was a loving husband, father and grandfather. He and his best friend and wife, Denise (Cross) Wartes celebrated 50 years of marriage in 2022. He loved and doted on his children, grandchildren and family.

Mark grew up in Utqiagvik, where he maintained lifelong friends and family. He attended school in Utqiagvik, Alaska, Sequim, Washington, and Seattle, Washington, and college at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, North Carolina, where he was a member of the winning soccer team.

After his Air Force military service in Bitburg, Germany, he returned home to his beloved Arctic and lived at the Colville River Delta. While living in the Arctic, he maintained a subsistence lifestyle, worked with various oil companies, including helping build the first temporary oil drilling ice island, guided numerous researchers across the slope in the early days of building the trans-Alaska pipeline as they established baseline studies of various species, land and water formations. Mark and his wife Denise lived there several years before moving south to Fairbanks, where they continued to raise their children, Marwan Wartes and Marita (Wartes) Bunch.

In Fairbanks, Mark owned a commercial floor covering company, where he and his brother, Eldon, worked all across Alaska, eventually retiring to serve several years as the general manager of Water Wagon, a local family owned water delivery company.

As a private pilot and registered big game guide, Mark flew and hunted along the Arctic coast and the Brooks Range of Alaska. He then spent a number of summers as a fishing boat captain in Valdez in Prince William Sound.

He and his brother, Eldon, coached a number of youth soccer and hockey teams, along with playing hockey himself with the Fairbanks Old Timers hockey team for several years.

He was a proud and active member of the Fairbanks Presbyterian Church and Yukon Presbytery, serving as the Presbytery Native American liaison for many years, along with being involved with Bingle Memorial Camp.

He enjoyed dancing with his beloved Pavva Inupiaq Dance group, involving his wife and grandchildren in the group, and performing locally many times.

He is survived by his much loved wife, Denise (Cross) Wartes, son Marwan and wife Erin, daughter Marita and husband Matthew Bunch, beloved Aapa to grandchildren Gwendolyn, Owen, Blake, and Trevor Bunch, and Matia Wartes. He was so pleased that all of his siblings came to visit him recently: Merrily Lowry (Steve), Teena Helmericks (Jim), Marti Bennett (Richard), Clayton Wartes (Judy), and Eldon Wartes (Debbie). Also surviving are many nieces, nephews, cousins and friends.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made in memory of Mark Wartes to the University of Alaska Fairbanks in support of the Wartes Rural Alaska Honors Institute scholarship. Contributions may be made online at bit.ly/3wHPvqK . Checks can also be mailed to: UAF Development and Alumni Relations, PO Box 757530, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775. Please make checks payable to "UA Foundation" and include "In memory of Mark Wartes" in the memo. If you have questions, contact the UAF Development and Alumni Relations at (907) 474-2619.

Several members of his family are traveling to Utqiagvik to attend Kivgiq Feb. 2-5, 2023, to celebrate his beloved Arctic. A memorial service is being planned in Fairbanks on May 20, 2023, with final burial on the Arctic coast.

Funeral arrangements were entrusted to Fairbanks Funeral Home.

Condolences can be sent to the family at: denisewartes@yahoo.com, or 1713 Central Ave., Fairbanks, AK 99709.

There are currently no tributes.

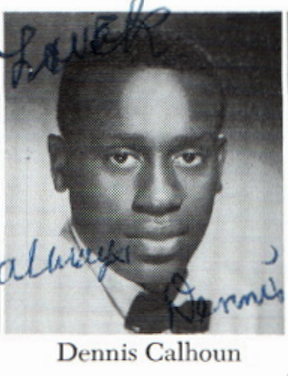

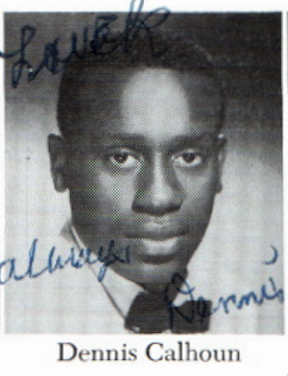

Dennis Lee Calhoun

Birth Date:

1945-12-13

Deceased Date:

2023-01-15

Don Deschenes

- May 6th, 2024

Dennis was always smiling and he did have a big smile. After high school he played ball at Skagit Valley. He had the perfect body for basketball with his long arms and legs. His brother John (65) passed away also.

Gloria G Jaeckel (Haight)

Birth Date:

1946-05-06

Deceased Date:

2022-09-25

Obituary:

Gloria Haight Jaekel

May 6, 1946 - September 25, 2022

Puyallup, Washington - Gloria Gail Jaekel was born in Seattle, WA to parents Francis E Haight and Gloria Haight.

She was preceded in death by her beloved son Jason, who died in a tragic car accident at age 17. She is survived by her sister, Carol Drennen, her brother Bob Haight, her niece Roxanne (Robert) Kangas, great-nephews Roland and Reid Kangas from Seattle, Washington and Ty Mireles of Rosyln, Washington.

Gloria Haight Jaekel

May 6, 1946 - September 25, 2022

Puyallup, Washington - Gloria Gail Jaekel was born in Seattle, WA to parents Francis E Haight and Gloria Haight.

She was preceded in death by her beloved son Jason, who died in a tragic car accident at age 17. She is survived by her sister, Carol Drennen, her brother Bob Haight, her niece Roxanne (Robert) Kangas, great-nephews Roland and Reid Kangas from Seattle, Washington and Ty Mireles of Rosyln, Washington.

There are currently no tributes.

Linda Jean Martos (LaBranche)

Birth Date:

1946-10-19

Deceased Date:

2022-09-10

Obituary:

Linda Jean Martos, daughter of Dolphis and Evelyn LaBranche was born October 19, 1946 in Seattle, Washington. She passed away September 10, 2022 with her two daughters by her side. Linda will be remembered for being very strong mentally, emotionally and having a strong work ethic which was the foundation of her life. Her daughters were lucky to have such an amazing role model and her one-of-a kind legacy will live on forever.

As an independent Christian woman, not only was Linda a bright light, but she was also caring, compassionate, loving, giving, thoughtful and all-welcoming to everyone she met. Her sense of humor was always on display but her wise, straight to the point advice was spot on especially when she had to be the peacemaker. Simply stated, Linda was a beautiful and amazing woman and all who knew her were thankful to have Linda in their lives.

Linda left an indelible impact on the lives of countless by either greeting you at the door, sharing a laugh while being the "Garden Lady", or sending out seasonal/holiday cards to those who were special to her. Over the years, her hands could be found in a pot of soil or in the yard where she loved tending to plants and flowers while making her home look and feel amazing! Christmas was a special time for Linda and her daughters as each year she was proud to set up her hand-painted Christmas Village which consisted of hundreds of ceramic decorations. Linda truly had a creative mind and was able to masterfully blend colors together. A true talent!

Linda was preceded in death by her father (Dolphis), mother (Evelyn), her two sisters (Shirley & Jerri), her brother (Ron) and her daughter (Nicole). Linda is survived by her daughters (Lynnette and Teresa) and extended family.

A celebration of life will be held from 12:00 PM to 3:00 PM on October 19, 2022 at Taylor Creek Church, 21110 244th Ave. SE, Maple Valley, Washington 98038.

Linda Jean Martos, daughter of Dolphis and Evelyn LaBranche was born October 19, 1946 in Seattle, Washington. She passed away September 10, 2022 with her two daughters by her side. Linda will be remembered for being very strong mentally, emotionally and having a strong work ethic which was the foundation of her life. Her daughters were lucky to have such an amazing role model and her one-of-a kind legacy will live on forever.

As an independent Christian woman, not only was Linda a bright light, but she was also caring, compassionate, loving, giving, thoughtful and all-welcoming to everyone she met. Her sense of humor was always on display but her wise, straight to the point advice was spot on especially when she had to be the peacemaker. Simply stated, Linda was a beautiful and amazing woman and all who knew her were thankful to have Linda in their lives.

Linda left an indelible impact on the lives of countless by either greeting you at the door, sharing a laugh while being the "Garden Lady", or sending out seasonal/holiday cards to those who were special to her. Over the years, her hands could be found in a pot of soil or in the yard where she loved tending to plants and flowers while making her home look and feel amazing! Christmas was a special time for Linda and her daughters as each year she was proud to set up her hand-painted Christmas Village which consisted of hundreds of ceramic decorations. Linda truly had a creative mind and was able to masterfully blend colors together. A true talent!

Linda was preceded in death by her father (Dolphis), mother (Evelyn), her two sisters (Shirley & Jerri), her brother (Ron) and her daughter (Nicole). Linda is survived by her daughters (Lynnette and Teresa) and extended family.

A celebration of life will be held from 12:00 PM to 3:00 PM on October 19, 2022 at Taylor Creek Church, 21110 244th Ave. SE, Maple Valley, Washington 98038.

There are currently no tributes.

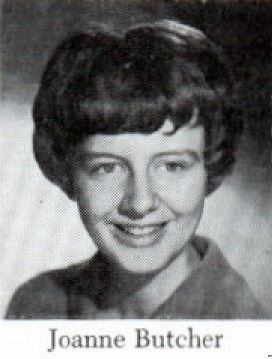

Joanne Butcher

Deceased Date:

2022-07-12

There are currently no tributes.

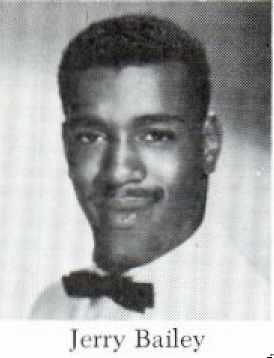

Jerry Glenn Bailey

Birth Date:

1946-03-16

Deceased Date:

2022-04-23

Don Deschenes

- January 3rd, 2024

I enjoyed trying to tackle him which never happened. He was a great half back who played in the NFL. He went onto Columbia River and was named Junior College All American along with O.J. Simpson the other half back.

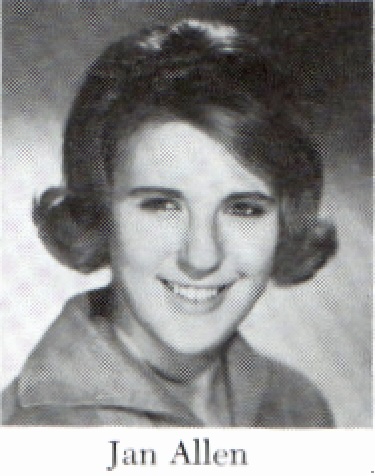

Jan Marshall (Allen)

Birth Date:

1946-10-16

Deceased Date:

2022-03-26

Obituary:

Mrs. Janet “Jan” Marshall of Black Diamond WA, passed away on Saturday, March 26th, 2022, at the age of 75

Jan was born to parents Fred and Marie Allen on October 16, 1946, in Seattle, WA. She grew up the middle daughter of 4 and attended Cleveland High School class of 1964. In 1966, she married her sweetheart of 55 years, Chuck. The couple welcomed their son Jerald “JB” Marshall in the spring of 1977. The family resided in the Covington / Black Diamond area for 48+ years.

Jan was an accomplished hair stylist who opened her first salon in her home, she went onto open two additional retail salons and retired after 52 years in October 2017. Jan was a stylist, stylist with lifelong multi generation clientele. She loved her career and the friendships she made from it. On Sundays for a little bit over 20 years Jan led a convoy of shuttlers at Avis rental car. She was voluntold to retire after getting caught doing donuts in the shuttle van. In retirement Jan was an active and dedicated member of TREA and served as Chaplin up until her passing.

Jan enjoyed camping, ocean beaches, a warm bath with a good book and spending time with family and friends. She loved being a mom and was a devoted wife, she was an auntie and nanna to many, and adored by dozens. Jan was a natural helper at heart, with a loving, kind, and witty personality – her laugh was infectious. Without hesitation she made time to lend her support for others. She will be greatly missed, but she will always be in our hearts and memories.

Jan is survived by her husband, Chuck Marshall; son, Jerald Marshall; future daughter-in-law Nancy; brother, Randy Allen; sisters, Judie Keblish, Robin Campbell, and Donna Copp; niece, Janine Keblish; and nephew, John Michael Keblish;

Jan is also survived by her aunt, Shirley Ward; and uncle, George Nelson; along with several cousins, nieces, nephews, and in-laws.

A memorial service is scheduled for 10:30am on May 6th at Tahoma National Cemetery with a reception to follow. All are welcome to attend and celebrate Momma Jan's life. In lieu of flowers, please send donations to https://diabetes.org/

https://curnowfuneralhome.com/tribute/details/261656/Janet-Marshall/obituary.html

Mrs. Janet “Jan” Marshall of Black Diamond WA, passed away on Saturday, March 26th, 2022, at the age of 75

Jan was born to parents Fred and Marie Allen on October 16, 1946, in Seattle, WA. She grew up the middle daughter of 4 and attended Cleveland High School class of 1964. In 1966, she married her sweetheart of 55 years, Chuck. The couple welcomed their son Jerald “JB” Marshall in the spring of 1977. The family resided in the Covington / Black Diamond area for 48+ years.

Jan was an accomplished hair stylist who opened her first salon in her home, she went onto open two additional retail salons and retired after 52 years in October 2017. Jan was a stylist, stylist with lifelong multi generation clientele. She loved her career and the friendships she made from it. On Sundays for a little bit over 20 years Jan led a convoy of shuttlers at Avis rental car. She was voluntold to retire after getting caught doing donuts in the shuttle van. In retirement Jan was an active and dedicated member of TREA and served as Chaplin up until her passing.

Jan enjoyed camping, ocean beaches, a warm bath with a good book and spending time with family and friends. She loved being a mom and was a devoted wife, she was an auntie and nanna to many, and adored by dozens. Jan was a natural helper at heart, with a loving, kind, and witty personality – her laugh was infectious. Without hesitation she made time to lend her support for others. She will be greatly missed, but she will always be in our hearts and memories.

Jan is survived by her husband, Chuck Marshall; son, Jerald Marshall; future daughter-in-law Nancy; brother, Randy Allen; sisters, Judie Keblish, Robin Campbell, and Donna Copp; niece, Janine Keblish; and nephew, John Michael Keblish;

Jan is also survived by her aunt, Shirley Ward; and uncle, George Nelson; along with several cousins, nieces, nephews, and in-laws.

A memorial service is scheduled for 10:30am on May 6th at Tahoma National Cemetery with a reception to follow. All are welcome to attend and celebrate Momma Jan's life. In lieu of flowers, please send donations to https://diabetes.org/

https://curnowfuneralhome.com/tribute/details/261656/Janet-Marshall/obituary.html

Don Deschenes

- December 21st, 2023

Enjoyed spending lunch with Jan. We were on grounds patrol and were supposed to stop people from bringing food outside of lunchroom. I don't think we ever stopped anyone.

Worked with her Mom at Sears while I was in college.

Richard Arthur (Rich) Pascoe

Birth Date:

1946-02-25

Deceased Date:

2022-03-14

Obituary:

Following a brief illness, Richard Arthur Pascoe passed away on March 14, 2022. Rich was born on February 25, 1946 in Seattle, WA to Will and Annette (Selle) Pascoe. After graduating from Cleveland High School and attending Central Washington University, he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1966 and was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany for 2 ½ years. That same year, he married Rosalind (Kinison); they had two children, Renee (Pascoe) O'Brien and Ross Pascoe. In 1977 Richard married Sharon (Everts) Pascoe and had a daughter, Angela (Pascoe) Shelley. Rich and Sharon later divorced but remained life-long friends and partners. Rich lived for much of the last 35 years in Arkansas, but also enjoyed spending time on Whidbey Island in Washington State. We will miss Rich's wit, his boisterous nature and his legendary stories.

A Celebration of Life for Rich will be held, Saturday, August 6, 2022, 1:00 p.m. on Whidbey Island. Contact us through the online obituary below for information.

https://my.gather.app/remember/richard-pascoe to share your thoughts and memories and sign the online guest register.

Following a brief illness, Richard Arthur Pascoe passed away on March 14, 2022. Rich was born on February 25, 1946 in Seattle, WA to Will and Annette (Selle) Pascoe. After graduating from Cleveland High School and attending Central Washington University, he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1966 and was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany for 2 ½ years. That same year, he married Rosalind (Kinison); they had two children, Renee (Pascoe) O'Brien and Ross Pascoe. In 1977 Richard married Sharon (Everts) Pascoe and had a daughter, Angela (Pascoe) Shelley. Rich and Sharon later divorced but remained life-long friends and partners. Rich lived for much of the last 35 years in Arkansas, but also enjoyed spending time on Whidbey Island in Washington State. We will miss Rich's wit, his boisterous nature and his legendary stories.

A Celebration of Life for Rich will be held, Saturday, August 6, 2022, 1:00 p.m. on Whidbey Island. Contact us through the online obituary below for information.

https://my.gather.app/remember/richard-pascoe to share your thoughts and memories and sign the online guest register.

There are currently no tributes.

Benjamin (Ben) Dennis Grenn

Birth Date:

1946-02-22

Deceased Date:

2021-12-08

Obituary:

Benjamin "Ben" Dennis Grenn, age 75, passed away at his residence in Anchorage, Alaska, on Dec. 7, 2021, after a 14-month battle with brain cancer. He was born on Feb. 22, 1946, in Aberdeen, Wash., to Joseph and Iona Grenn. The family moved to Seattle, Wash., in 1949, where Ben was blessed with two younger sisters, Nancy Nicholson and Gail Grenn. On Jan. 18, 1969, Ben married Selinda Tollefsen in Anchorage.

In addition to serving four years in the U.S. Air Force, Ben had myriad of fascinating jobs – he was an elementary school teacher, sports news anchor, newspaper writer, a radio personality and worked for the State of Alaska for many years as staff to a variety of colorful state legislators. But most importantly, he was a loving husband, father, uncle, brother and grandfather. Ben's first love was his family, but a close second was his love for sports of all kinds, particularly Seattle sports.

Ben is survived by his wife, Selinda Tollefsen Grenn; their children, Carrie Craig (Grenn) with husband Shane and son Craig Murphy, Skyler Grenn with wife Amanda and their children Aurora and Aria, Jason Grenn with wife Jana and their children Atticus, Vivienne and Truman; sisters, Nancy Nicholson and her sons Colby and Austin and their families and Gail Grenn.

In lieu of flowers, the family encourages donations to ANCORA Home Health and Hospice or the American Cancer Society - Alaska.

A memorial service will be held at Baxter Road Bible Church in Anchorage on Saturday, Jan. 29, 2022, at 1 p.m., with a reception afterward.

Benjamin "Ben" Dennis Grenn, age 75, passed away at his residence in Anchorage, Alaska, on Dec. 7, 2021, after a 14-month battle with brain cancer. He was born on Feb. 22, 1946, in Aberdeen, Wash., to Joseph and Iona Grenn. The family moved to Seattle, Wash., in 1949, where Ben was blessed with two younger sisters, Nancy Nicholson and Gail Grenn. On Jan. 18, 1969, Ben married Selinda Tollefsen in Anchorage.

In addition to serving four years in the U.S. Air Force, Ben had myriad of fascinating jobs – he was an elementary school teacher, sports news anchor, newspaper writer, a radio personality and worked for the State of Alaska for many years as staff to a variety of colorful state legislators. But most importantly, he was a loving husband, father, uncle, brother and grandfather. Ben's first love was his family, but a close second was his love for sports of all kinds, particularly Seattle sports.

Ben is survived by his wife, Selinda Tollefsen Grenn; their children, Carrie Craig (Grenn) with husband Shane and son Craig Murphy, Skyler Grenn with wife Amanda and their children Aurora and Aria, Jason Grenn with wife Jana and their children Atticus, Vivienne and Truman; sisters, Nancy Nicholson and her sons Colby and Austin and their families and Gail Grenn.

In lieu of flowers, the family encourages donations to ANCORA Home Health and Hospice or the American Cancer Society - Alaska.

A memorial service will be held at Baxter Road Bible Church in Anchorage on Saturday, Jan. 29, 2022, at 1 p.m., with a reception afterward.

Don Deschenes

- January 4th, 2024

Most memorable moment was West Seattle double overtime game. Ben had a starter pistol so everyone could hear the end of the game. During the celebration after the victory he pointed starters pistol at two cops, I overheard the cops tell Coach Scott they will shoot him next time he does that.

James (Jim) Lloyd Bianchi

Birth Date:

1946-04-02

Deceased Date:

2021-07-15

Obituary:

James "Jim" Lloyd Bianchi passed away in his home in Sun Lakes, AZ, July 15, 2021. Jim was born April 3, 1946 in Seattle, WA to Larry & Lois Bianchi. He married his childhood sweetheart and beloved wife, Pam. Jim & Pam raised their 3 children in their hometown of Seattle, WA. He was a loving husband, father, grandfather "Papa", brother and uncle. He is survived by his loving wife Pam and their two children, Kimberly (R.J.) and Paul (Brooke) and his brother Larry (Zoey). He will be missed by his grandchildren, Ryan, Jacob, Olivia & Chloe, and several brother and sister-in-laws, nieces and nephews. He is now at peace with his son Mark. Funeral Mass will be held Saturday, July 31, 2021, 1:00pm, St. George Catholic Church, Seattle, WA.

James "Jim" Lloyd Bianchi passed away in his home in Sun Lakes, AZ, July 15, 2021. Jim was born April 3, 1946 in Seattle, WA to Larry & Lois Bianchi. He married his childhood sweetheart and beloved wife, Pam. Jim & Pam raised their 3 children in their hometown of Seattle, WA. He was a loving husband, father, grandfather "Papa", brother and uncle. He is survived by his loving wife Pam and their two children, Kimberly (R.J.) and Paul (Brooke) and his brother Larry (Zoey). He will be missed by his grandchildren, Ryan, Jacob, Olivia & Chloe, and several brother and sister-in-laws, nieces and nephews. He is now at peace with his son Mark. Funeral Mass will be held Saturday, July 31, 2021, 1:00pm, St. George Catholic Church, Seattle, WA.

There are currently no tributes.

Steve Theron Burnum

Birth Date:

1946-07-18

Deceased Date:

2020-11-06

Greg Rafanelli

- May 7th, 2024

I remember enjoying Saturday Night Hour at the NAS Whidbey Island Officer's Club. We served there together in the Naval Reserve for 10 years.

Greg Rafanelli

- February 28th, 2024

I met Steve in 1983 at NAS Whidbey Island. We were both Navy Reservists and would occasionally have a beer together at the Officer's Club on Friday and/or Saturday nights. We were both Lieutenant Commanders at the time. He was a Naval Flight Officer, a former Bombardier Navigator in the A-6 Intruder. I recalled to Active duty in 1987 and didn't see him after the Navy moved me to New York in 1989.

Frank Cooper

Birth Date:

1946-04-13

Deceased Date:

2020-04-16

Obituary:

Frank was born and raised on South Beacon Hill. He enjoyed sports and fishing and hanging out in Georgetown & Southpark.

He attended Cleveland High School and Highline Jr. College before joining the Airforce.

Frank was preceded in death by his parents, Frank and Eva, and is survived by his sister, Donna.

Sign Frank's online Guest Book at www.Legacy.com

Frank was born and raised on South Beacon Hill. He enjoyed sports and fishing and hanging out in Georgetown & Southpark.

He attended Cleveland High School and Highline Jr. College before joining the Airforce.

Frank was preceded in death by his parents, Frank and Eva, and is survived by his sister, Donna.

Sign Frank's online Guest Book at www.Legacy.com

Greg Rafanelli

- May 7th, 2024

Corky was like a brother. Our Mom's grew up as next-door neighbors on Beacon Hill. My Mom Lena Donadel was a Bridesmaid at Eva and Frank Cooper's Wedding at St. Peter's Church.

Greg Rafanelli

- February 28th, 2024

Corky was like a brother to me. Our mothers grew up next door neighbors in Garlic Gulch as did Marie Bellotti's mom Florence. Corky, Marie and I were all in the same Confirmation Class at St. Peter's in 1958. My Mom was a bridesmaid in Frank and Eva's wedding. I still have a colored video of that event and also Corky when he was a baby.

Don Deschenes

- January 7th, 2024

Frank was a great football player. He weighed 190 pounds and it was all muscle. Similar weight today would be about 270 pounds. He was a great pulling guard and nose tackle. Frank, Bill Landry, Jerry Bailey and myself were the only junior starters on the 63 football team which only lost 2 games and beat Franklin for the first time in 27 years. Franklin had two players (Tom Greenlee and Dave Dinish) that played for UW. Tom was a con-census All American at defensive end.

Richard (Dick) James Longo

Birth Date:

1946-06-20

Deceased Date:

2020-04-10

Obituary:

Richard J. “Chef Deacon” Longo, age 73, passed away peacefully at home in Bellingham after a long battle with pulmonary fibrosis. Dick was born June 20, 1946 in Spokane, WA to Leonard and Mary Longo. Dick graduated from Cleveland High School in Seattle and learned to be a chef in the US Navy for six years. He proudly served on the USS Dixie during the Vietnam War. Dick married Elizabeth “Betsy” Jones on September 11, 1971 in Seattle. Dick was an executive chef in the Seattle area until the family moved to Bellingham in 1979. He retired after 13 years at Boss Tweed Catering. Dick and Betsy have been active members of Church of the Assumption since 1979. Dick enjoyed watching his children and grandchildren’s sports, following the Huskies and Seahawks, and cooking for his family and friends. He will be remembered as a loving husband and father, and a wonderful and active grandfather and great-grandfather. He is survived by his loving wife of 49 years, Betsy, son Nic (Grace) Longo, daughter Kelly Freeman (Curt Sleasman), grandchildren Kendra (Wade), Kaleb, Noah, Gabriel, Emilia, Stephanie, Christopher, Sidney and Parker, great-grandchildren Ivy and Leah, sister Bobbi, brother Patrick, and many loving relatives and friends. Mass of Christian Burial will be held at Church of the Assumption in Bellingham at a later date. Memorials may be made to Whatcom Hospice attention: Massage Program. You may share memories with the family at www.westfordfuneralhome.com.

Richard J. “Chef Deacon” Longo, age 73, passed away peacefully at home in Bellingham after a long battle with pulmonary fibrosis. Dick was born June 20, 1946 in Spokane, WA to Leonard and Mary Longo. Dick graduated from Cleveland High School in Seattle and learned to be a chef in the US Navy for six years. He proudly served on the USS Dixie during the Vietnam War. Dick married Elizabeth “Betsy” Jones on September 11, 1971 in Seattle. Dick was an executive chef in the Seattle area until the family moved to Bellingham in 1979. He retired after 13 years at Boss Tweed Catering. Dick and Betsy have been active members of Church of the Assumption since 1979. Dick enjoyed watching his children and grandchildren’s sports, following the Huskies and Seahawks, and cooking for his family and friends. He will be remembered as a loving husband and father, and a wonderful and active grandfather and great-grandfather. He is survived by his loving wife of 49 years, Betsy, son Nic (Grace) Longo, daughter Kelly Freeman (Curt Sleasman), grandchildren Kendra (Wade), Kaleb, Noah, Gabriel, Emilia, Stephanie, Christopher, Sidney and Parker, great-grandchildren Ivy and Leah, sister Bobbi, brother Patrick, and many loving relatives and friends. Mass of Christian Burial will be held at Church of the Assumption in Bellingham at a later date. Memorials may be made to Whatcom Hospice attention: Massage Program. You may share memories with the family at www.westfordfuneralhome.com.

There are currently no tributes.

Jeffery (Jeff) Lewis Nack

Birth Date:

1945-11-15

Deceased Date:

2020-02-25

Obituary:

Passed away peacefully with his family by his side on February 25, 2010 after a valiant 8-month battle with pancreatic cancer.

Jeff grew up in Seattle and graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. He served in Vietnam before joining the USAFR as a flight engineer with the 313th MAS retiring after 20 years.

He resided with his family in Olalla for over 40 years where he became a member of the Olalla Polar Bear Club.

Jeff worked in HVAC sales and service, retiring in 2008. His favorite pastimes were golfing, traveling, camping, football and playing darts at VFW Post 2669, where he had many friends.

Jeff is survived by his beloved wife Linda of 44 years, 3

daughters: Karen (Dennis), Debbie (Jason) and Lori, 5

grandchildren: Brianna, Irene, Marissa, Jalyn and Travis and 1

great-grandchild Maleah. Jeff was also a caring brother, uncle and friend.

Passed away peacefully with his family by his side on February 25, 2010 after a valiant 8-month battle with pancreatic cancer.

Jeff grew up in Seattle and graduated from Cleveland High School in 1964. He served in Vietnam before joining the USAFR as a flight engineer with the 313th MAS retiring after 20 years.

He resided with his family in Olalla for over 40 years where he became a member of the Olalla Polar Bear Club.

Jeff worked in HVAC sales and service, retiring in 2008. His favorite pastimes were golfing, traveling, camping, football and playing darts at VFW Post 2669, where he had many friends.

Jeff is survived by his beloved wife Linda of 44 years, 3

daughters: Karen (Dennis), Debbie (Jason) and Lori, 5

grandchildren: Brianna, Irene, Marissa, Jalyn and Travis and 1

great-grandchild Maleah. Jeff was also a caring brother, uncle and friend.

There are currently no tributes.

Barry E Knake

Birth Date:

1946-10-01

Deceased Date:

2020-02-10

Obituary:

Barry was born in Chicago, IL on October 1, 1946 to Betty and Louis Knake. He passed at age of 73, on February 10, 2020. Barry earned his M.S. in Psychology in 1971. His professional career: Industrial Psychologist, consulting executive; U.S. OPM, Seattle Region; and President of KMB Associates. Barry was an avid swimmer at local public pools. He is survived by wife and soulmate, Pamela Knake, his children Sean, Ryan, Julene (tweety), stepdaughters Heleena (Ahanu), Leona (Raul), Venessa, 13 grandchildren, 2 great-grandchildren. His life touched so many leaving us all treasured memories. His service will be held at Bonnie-Watson (SeaTac), Thursday, February 27, 11:00am.

Barry was born in Chicago, IL on October 1, 1946 to Betty and Louis Knake. He passed at age of 73, on February 10, 2020. Barry earned his M.S. in Psychology in 1971. His professional career: Industrial Psychologist, consulting executive; U.S. OPM, Seattle Region; and President of KMB Associates. Barry was an avid swimmer at local public pools. He is survived by wife and soulmate, Pamela Knake, his children Sean, Ryan, Julene (tweety), stepdaughters Heleena (Ahanu), Leona (Raul), Venessa, 13 grandchildren, 2 great-grandchildren. His life touched so many leaving us all treasured memories. His service will be held at Bonnie-Watson (SeaTac), Thursday, February 27, 11:00am.

There are currently no tributes.

James Dayton Schafer

Birth Date:

1946-01-11

Deceased Date:

2019-11-28

Obituary:

It is with great sadness that after a long struggle with cancer, the family of James Dayton Schafer announces his passing on November 28, 2019 in his home surrounded by family. Admired by all who knew him for his deep love and compassion for family and friends and an abiding faith. He possessed a quick wit, sarcastic sense of humor and the gift of being a true and loyal friend. Jim enjoyed fishing, camping, traveling, collecting art, and watching sports. Was involved in the Highline Exchange Club for over 40 years. He graduated from Cleveland High School 1964 and lived in Renton and Auburn. Owner of Schafer & Husmoe, a CPA practice in Burien.

Survived by his loving wife of 53 years, Tina Schafer. His children Tina, Troy, Torey, 5 grandchildren, 4 brothers, 3 sisters and all their families.

It is with great sadness that after a long struggle with cancer, the family of James Dayton Schafer announces his passing on November 28, 2019 in his home surrounded by family. Admired by all who knew him for his deep love and compassion for family and friends and an abiding faith. He possessed a quick wit, sarcastic sense of humor and the gift of being a true and loyal friend. Jim enjoyed fishing, camping, traveling, collecting art, and watching sports. Was involved in the Highline Exchange Club for over 40 years. He graduated from Cleveland High School 1964 and lived in Renton and Auburn. Owner of Schafer & Husmoe, a CPA practice in Burien.

Survived by his loving wife of 53 years, Tina Schafer. His children Tina, Troy, Torey, 5 grandchildren, 4 brothers, 3 sisters and all their families.

There are currently no tributes.

Judith Ann Shoup

Birth Date:

1946-07-29

Deceased Date:

2019-09-14

Obituary:

Judith A. Shoup Obituary

Judith Ann Shoup of Ketchikan, AK passed away Saturday, September 14, 2019 at the age of 73. She had a long and courageous fight with cancer but eventually succumbed peacefully at Whatcom Hospice House in Bellingham, WA. Memorial services will be held at 11:00 AM on Saturday, October 19, 2019 at Flintofts Funeral Home, 540 E Sunset Way, Issaquah, WA Judy was born on July 29, 1946 in Forsyth, Montana, the daughter of William A. and Eleanor M. Shoup. Her parents operated a cattle ranch near Ingomar, Montana, but they were separated when her mother returned to Washington to raise her five children, first in Arlington, then in Carnation near her grandparents dairy farm, where she attended school until the middle of 8th grade. The family moved to Seattle when her mother got her college degree and started working for Boeing, where she finished her education earning a diploma from Cleveland High School in 1964. Judy was a free spirit and liked to move around or relocate. First to Switzerland where she lived for a couple years, then San Francisco and St. Thomas (US Virgin Islands) before settling in Alaska, where she lived first in Juneau then in Ketchikan until her death. Judy devoted her life to raising her son, Dana and was devastated by his sudden death in 2018. She raised him as a single mother when the idea was not popular or common. Survivors include three of her five siblings: Linda J. Shoup of Renton, Dale W. Shoup of Edmonds, and Roy E. Shoup of Mountlake Terrace in addition to four nieces and nephews: David A. Shoup of Tacoma, Philip A. Shoup of Seattle, Kelsey Foster of Edmonds, and Aaron Shoup of Tallahassee, Florida. Friends and relatives are invited to share memories and sign the familys on-line guest book at www.flintofts.com In lieu of flowers, please consider making a donation to the American Cancer Society on Judiths behalf.

Judith A. Shoup Obituary

Judith Ann Shoup of Ketchikan, AK passed away Saturday, September 14, 2019 at the age of 73. She had a long and courageous fight with cancer but eventually succumbed peacefully at Whatcom Hospice House in Bellingham, WA. Memorial services will be held at 11:00 AM on Saturday, October 19, 2019 at Flintofts Funeral Home, 540 E Sunset Way, Issaquah, WA Judy was born on July 29, 1946 in Forsyth, Montana, the daughter of William A. and Eleanor M. Shoup. Her parents operated a cattle ranch near Ingomar, Montana, but they were separated when her mother returned to Washington to raise her five children, first in Arlington, then in Carnation near her grandparents dairy farm, where she attended school until the middle of 8th grade. The family moved to Seattle when her mother got her college degree and started working for Boeing, where she finished her education earning a diploma from Cleveland High School in 1964. Judy was a free spirit and liked to move around or relocate. First to Switzerland where she lived for a couple years, then San Francisco and St. Thomas (US Virgin Islands) before settling in Alaska, where she lived first in Juneau then in Ketchikan until her death. Judy devoted her life to raising her son, Dana and was devastated by his sudden death in 2018. She raised him as a single mother when the idea was not popular or common. Survivors include three of her five siblings: Linda J. Shoup of Renton, Dale W. Shoup of Edmonds, and Roy E. Shoup of Mountlake Terrace in addition to four nieces and nephews: David A. Shoup of Tacoma, Philip A. Shoup of Seattle, Kelsey Foster of Edmonds, and Aaron Shoup of Tallahassee, Florida. Friends and relatives are invited to share memories and sign the familys on-line guest book at www.flintofts.com In lieu of flowers, please consider making a donation to the American Cancer Society on Judiths behalf.

There are currently no tributes.

Gerald Joseph "Jerry" Gribble

Birth Date:

1931-03-28

Deceased Date:

2019-02-03

Obituary:

BIRTH

28 Mar 1931

Seattle, King County, Washington, USA

DEATH

3 Feb 2019 (aged 87)

Bellevue, King County, Washington, USA

BURIAL

Cremated

MEMORIAL ID

220839576 · View Source

MEMORIAL

PHOTOS 1

FLOWERS 1

Gerald Joseph Gribble was born March 28, 1931 in Seattle Washington, the fourth, third, surviving son of Vance, a Seattle Fire Dept. Captain and Ida (Lapisin) Gribble the Traditional homemaker. With English and Italian heritage, Jerry became rooted in Seattle’s Rainier Valley district most of his youth. In the Columbia City neighborhood, he found a group of aunts, uncles and cousins and neighbors who shared close family/friend ties and work ethic.

The Dominican Nuns at St. Edwards School and the Holy Names Nuns at St. Mary’s School convinced Jerry at an early age that there was two ways to get a good education - Sisters way or Sisters way. He frequently served as an altar boy at daily mass, always monitored and encouraged by his mother. He also assisted in the ministering to Italian Prisoners of War at several camps in the Seattle Tacoma area during the 40’s.

The old family upright piano served as a starting point for developing a natural talent, something by his own admission he never fully developed. He also played the Accordion, and was self-taught on the Organ, a skill he volunteered at for churches over a 60-year period. He always said, “music is a vocation, not a vacation”.

In the early 40’s World War II began, and his brothers, Vance Jr. and Bob joined the Military. With a national manpower shortage; Jerry, tall for his age, found it easy to become an employee at age 10. He peddled his bicycle to a murrain of “starter” jobs.

Jerry graduated from St. Mary's Elementary School in June of ’45 and in September entered St. Edwards Seminary. After six months a very homesick kid returned home. With his family living across the street from Franklin High School in the Fall of ’46 he enrolled at Franklin and a whirlwind of activities began centered around the Franklin Boys Band. Victor McClelland, the band director, became a close friend and career mentor.

In June of ’49 Jerry Graduated from Franklin High School and secured a beginners job with the Boing Co. In September “Mc” his Franklin Band teacher invited him to join a newly formed PeP Band he was director of at Seattle University. By participating he would receive a Tuition Grant to attend S.U.

The personal revolution began. He was academically unprepared and struggled. Activities flourished and he excelled! In the fall of ’50 he met Mary Margret Merriman, a transfer student from Spokane. There were many dances and parties and the academics improved; there was a “new seriousness” in his life!

During the summer of ’52 the dreaded “Draft” letter arrived from Uncle Sam and in September it was off to US ARMY Boot Camp at San Louis Obispo CA. March found his on a troop ship sailing the Pacific headed for the Korean Police Action.

Arriving in Japan he was assigned to Camp Fuji with the 24th Infantry Division A&R. (Activities and Recreation). “The Fuji Five” music group evolved and stayed together even through a later transfer to Korea. The Officers Clubs in the Pusan area had live music for the next 4 months. He returned home in May of ’54.

Jerry sent Mary an engagement ring from Korea and wedding plans began. They were married by Father Kelly S.J. on Sept 11, 1954 at Blessed Sacrament Church in Seattle. Jerry re-entering Seattle U. that fall as a full-time student while appreciating the benefit of the G.I Bill for Veterans, and Mary had an office job.

Jerry graduated in June of ’55 with a bachelor’s degree in education. He humbly referred to his degree as “Suma Cum Deo Gratis” (with great thanks to God) and the patience of the Jesuit Fathers at S.U. He was named to the “Who’s who in American Colleges and Universities in ’55.

Brian Joseph arrived in July of ’55 and Douglas Eugene July of ’56. The Gribble’s moved to their first home on the Capital Hill Area in the shadows of St. Joseph’s Church. Kevin Christopher joined “the boys” in 1958. Jerry tried the Territorial Sales and Sales Representation jobs with no great success or personal satisfaction. In the fall of 1960, he announced to Mary, the boys, and the cat, house and car payments “I'm going back to Seattle U to become a Teacher!”. With the G.I. Bill and reviving some Barbering skills for income. At the ripe age of 30 a Teaching Certificate was secured and in the fall of 61’ Jerry was Teaching Business Classes at Cleveland High School in Seattle. Part-time Counselor and Activities Coordinator signaled the need for administrative credentials, so off to Seattle University night school and the process for a master’s in education Degree acquired in 1969. Just about that time Mary decided to Teach and started full-time at Seattle University.

In ’67 The Gribble’s had moved to Mercer Island and when an opening for a Mercer Is. Vice Principle/Activity Coordinator open up in ’69 Jerry applied for and got the job. Three years of social unrest and challenges in the schools and community detoured Jerry back to the classroom teaching Marketing and DECA (Distributive Education) activities. He brought this program to Mercer Island High School and became a Teacher Forerunner in Washington State for the program. His efforts were recognized and rewarded by being named to the National Star DECA Hall of Fame. He continued to serve as Director of Vocational Education for the school district.

In a commitment to his dying Uncle Laurence, Jerry became the custodian for his Aunt Clara. Clara let it be she wanted to see Reno Nevada one more time! So, during a summer break, Mary and Jerry found two recliner chairs that would fit into his van, loaded Clara and Mom Gribble (sisters) and Mary and Jerry headed off to Reno. They got to and all survived! After a fall at home Clara lived the next 9 years in a nursing home on Mercer Island where Jerry made daily visits. For those who knew Clara, that was a challenge.

In the summer of ’82 Mary, Jerry and the “boys” traveled to Europe spending 4 weeks touring in a small motorhome. They even found and visited shirttail relatives in Venice, Italy. After returning home and while driving his Motorhome to an administrative retreat, a car crossed the center line crashing head on into the Motorhome. As the driver, Jerry received the most serious injuries, primarily neurological damage to his legs. His health deteriorated and he retired from teaching in June ’86.

Upon Gribble’s arriving on Mercer Island one of the first people to greet them was Fr. John Walch, pastor of St. Monica's Church. His inquiring conversation exposed Jerrys experience as Organist, and the following Sunday Jerry was playing the Organ at 8:00 Mass. Once Fr. Walch said to Jerry “There is someone I want you to meet,” namely Tom Tivnen and his BiG Baratone voice.

The “Tom and Jerry Show” was at the 5:00 Mass every Saturday for 25 years, plus the music at countless weddings and funerals. When the Tivnens moved to Chehalis WA., Jerry retired from regular services.

Jerry had a passion for helping the needy. For 20 years, every Tuesday he would cook 10-15 gallons of soup and delivered it to the homeless shelters. In Recent years he made daily runs to Krispy Kream Donuts in Issaquah and bring their leftovers to men's and women's shelters in Seattle. He would stop at garage and rummage sales to solicit unsold clothing and bring them to the shelters as well.

That activity evolved into his “buy low sell high” theme selling trinkets to real estate; which may have contributed to the Gribble’s changing their home address 9 times during their marriage. He claimed his van would go out of control if he passed by an Estate Sale!

Jerry enjoyed working with and for people and had a passion serving Godin his Catholic Church. Only circumstances would keep him from attending daily Mass, receiving Communion and saying the Rosary every day. He had a special devotion to Our Mother of Perpetual help.

BIRTH

28 Mar 1931

Seattle, King County, Washington, USA

DEATH

3 Feb 2019 (aged 87)

Bellevue, King County, Washington, USA

BURIAL

Cremated

MEMORIAL ID

220839576 · View Source

MEMORIAL

PHOTOS 1

FLOWERS 1

Gerald Joseph Gribble was born March 28, 1931 in Seattle Washington, the fourth, third, surviving son of Vance, a Seattle Fire Dept. Captain and Ida (Lapisin) Gribble the Traditional homemaker. With English and Italian heritage, Jerry became rooted in Seattle’s Rainier Valley district most of his youth. In the Columbia City neighborhood, he found a group of aunts, uncles and cousins and neighbors who shared close family/friend ties and work ethic.

The Dominican Nuns at St. Edwards School and the Holy Names Nuns at St. Mary’s School convinced Jerry at an early age that there was two ways to get a good education - Sisters way or Sisters way. He frequently served as an altar boy at daily mass, always monitored and encouraged by his mother. He also assisted in the ministering to Italian Prisoners of War at several camps in the Seattle Tacoma area during the 40’s.

The old family upright piano served as a starting point for developing a natural talent, something by his own admission he never fully developed. He also played the Accordion, and was self-taught on the Organ, a skill he volunteered at for churches over a 60-year period. He always said, “music is a vocation, not a vacation”.

In the early 40’s World War II began, and his brothers, Vance Jr. and Bob joined the Military. With a national manpower shortage; Jerry, tall for his age, found it easy to become an employee at age 10. He peddled his bicycle to a murrain of “starter” jobs.

Jerry graduated from St. Mary's Elementary School in June of ’45 and in September entered St. Edwards Seminary. After six months a very homesick kid returned home. With his family living across the street from Franklin High School in the Fall of ’46 he enrolled at Franklin and a whirlwind of activities began centered around the Franklin Boys Band. Victor McClelland, the band director, became a close friend and career mentor.

In June of ’49 Jerry Graduated from Franklin High School and secured a beginners job with the Boing Co. In September “Mc” his Franklin Band teacher invited him to join a newly formed PeP Band he was director of at Seattle University. By participating he would receive a Tuition Grant to attend S.U.

The personal revolution began. He was academically unprepared and struggled. Activities flourished and he excelled! In the fall of ’50 he met Mary Margret Merriman, a transfer student from Spokane. There were many dances and parties and the academics improved; there was a “new seriousness” in his life!

During the summer of ’52 the dreaded “Draft” letter arrived from Uncle Sam and in September it was off to US ARMY Boot Camp at San Louis Obispo CA. March found his on a troop ship sailing the Pacific headed for the Korean Police Action.

Arriving in Japan he was assigned to Camp Fuji with the 24th Infantry Division A&R. (Activities and Recreation). “The Fuji Five” music group evolved and stayed together even through a later transfer to Korea. The Officers Clubs in the Pusan area had live music for the next 4 months. He returned home in May of ’54.

Jerry sent Mary an engagement ring from Korea and wedding plans began. They were married by Father Kelly S.J. on Sept 11, 1954 at Blessed Sacrament Church in Seattle. Jerry re-entering Seattle U. that fall as a full-time student while appreciating the benefit of the G.I Bill for Veterans, and Mary had an office job.

Jerry graduated in June of ’55 with a bachelor’s degree in education. He humbly referred to his degree as “Suma Cum Deo Gratis” (with great thanks to God) and the patience of the Jesuit Fathers at S.U. He was named to the “Who’s who in American Colleges and Universities in ’55.

Brian Joseph arrived in July of ’55 and Douglas Eugene July of ’56. The Gribble’s moved to their first home on the Capital Hill Area in the shadows of St. Joseph’s Church. Kevin Christopher joined “the boys” in 1958. Jerry tried the Territorial Sales and Sales Representation jobs with no great success or personal satisfaction. In the fall of 1960, he announced to Mary, the boys, and the cat, house and car payments “I'm going back to Seattle U to become a Teacher!”. With the G.I. Bill and reviving some Barbering skills for income. At the ripe age of 30 a Teaching Certificate was secured and in the fall of 61’ Jerry was Teaching Business Classes at Cleveland High School in Seattle. Part-time Counselor and Activities Coordinator signaled the need for administrative credentials, so off to Seattle University night school and the process for a master’s in education Degree acquired in 1969. Just about that time Mary decided to Teach and started full-time at Seattle University.

In ’67 The Gribble’s had moved to Mercer Island and when an opening for a Mercer Is. Vice Principle/Activity Coordinator open up in ’69 Jerry applied for and got the job. Three years of social unrest and challenges in the schools and community detoured Jerry back to the classroom teaching Marketing and DECA (Distributive Education) activities. He brought this program to Mercer Island High School and became a Teacher Forerunner in Washington State for the program. His efforts were recognized and rewarded by being named to the National Star DECA Hall of Fame. He continued to serve as Director of Vocational Education for the school district.

In a commitment to his dying Uncle Laurence, Jerry became the custodian for his Aunt Clara. Clara let it be she wanted to see Reno Nevada one more time! So, during a summer break, Mary and Jerry found two recliner chairs that would fit into his van, loaded Clara and Mom Gribble (sisters) and Mary and Jerry headed off to Reno. They got to and all survived! After a fall at home Clara lived the next 9 years in a nursing home on Mercer Island where Jerry made daily visits. For those who knew Clara, that was a challenge.

In the summer of ’82 Mary, Jerry and the “boys” traveled to Europe spending 4 weeks touring in a small motorhome. They even found and visited shirttail relatives in Venice, Italy. After returning home and while driving his Motorhome to an administrative retreat, a car crossed the center line crashing head on into the Motorhome. As the driver, Jerry received the most serious injuries, primarily neurological damage to his legs. His health deteriorated and he retired from teaching in June ’86.

Upon Gribble’s arriving on Mercer Island one of the first people to greet them was Fr. John Walch, pastor of St. Monica's Church. His inquiring conversation exposed Jerrys experience as Organist, and the following Sunday Jerry was playing the Organ at 8:00 Mass. Once Fr. Walch said to Jerry “There is someone I want you to meet,” namely Tom Tivnen and his BiG Baratone voice.

The “Tom and Jerry Show” was at the 5:00 Mass every Saturday for 25 years, plus the music at countless weddings and funerals. When the Tivnens moved to Chehalis WA., Jerry retired from regular services.

Jerry had a passion for helping the needy. For 20 years, every Tuesday he would cook 10-15 gallons of soup and delivered it to the homeless shelters. In Recent years he made daily runs to Krispy Kream Donuts in Issaquah and bring their leftovers to men's and women's shelters in Seattle. He would stop at garage and rummage sales to solicit unsold clothing and bring them to the shelters as well.

That activity evolved into his “buy low sell high” theme selling trinkets to real estate; which may have contributed to the Gribble’s changing their home address 9 times during their marriage. He claimed his van would go out of control if he passed by an Estate Sale!

Jerry enjoyed working with and for people and had a passion serving Godin his Catholic Church. Only circumstances would keep him from attending daily Mass, receiving Communion and saying the Rosary every day. He had a special devotion to Our Mother of Perpetual help.

There are currently no tributes.

Richard William Ploe

Birth Date:

1945-11-15

Deceased Date:

2018-12-09

Obituary:

Died in San Francisco.

There are currently no tributes.

Ken Buckley

Birth Date:

1946-10-01

Deceased Date:

2018-12-06

Obituary:

Kenneth Buckley, passed away at the age of 72 of Cancer in Red Bluff, CA. Born to Harley and Alpharetta Buckley in Seattle, WA, October 1, 1946, and attend High School, some college and the school of hard knocks. He resided in Seattle, WA, Winchester Bay, OR and Red Bluff, CA. He was married to Shirley for 53 years. Ken worked for Diamond International, for 12 years, Construction work for 12 years, and owned KBC Metal Fabrication for 15 years. Ken enjoyed hunting, fishing, and camping, also black powder pistols. Ken had lots of friends. He was a good father and husband of 53 years. Ken is survived by his wife, Shirley; children, James (Rachael), Karman (Tammy) and Keith (Kim); 4 grandchildren and 7 great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his father Harley, mother Alpharetta and sister Betty Buckley

Published in Daily News on Dec. 6, 2018

Kenneth Buckley, passed away at the age of 72 of Cancer in Red Bluff, CA. Born to Harley and Alpharetta Buckley in Seattle, WA, October 1, 1946, and attend High School, some college and the school of hard knocks. He resided in Seattle, WA, Winchester Bay, OR and Red Bluff, CA. He was married to Shirley for 53 years. Ken worked for Diamond International, for 12 years, Construction work for 12 years, and owned KBC Metal Fabrication for 15 years. Ken enjoyed hunting, fishing, and camping, also black powder pistols. Ken had lots of friends. He was a good father and husband of 53 years. Ken is survived by his wife, Shirley; children, James (Rachael), Karman (Tammy) and Keith (Kim); 4 grandchildren and 7 great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his father Harley, mother Alpharetta and sister Betty Buckley

Published in Daily News on Dec. 6, 2018

There are currently no tributes.

David (Dave) Hopkins Swayne

Birth Date:

1946-04-17

Deceased Date:

2018-09-27

Obituary:

David Hopkins Swayne, 72, of Independence, Missouri passed away September 27, 2018 at his home after suffering from dementia and other health issues for several years. Memorial services will be held at 4:30 p.m. on Sunday, October 14, 2018 at Independence Central/Gospel Park Church of Jesus Christ, 919 S Delaware St, Independence, MO 64050.

David Hopkins Swayne was born on April 17, 1946 in Seattle, Washington. David went Concorde Elementary school in South Park by Boeing Field, then to Asa Mercer Junior High, moving on to Cleveland High School where he was the Yell King and Class President his senior year, graduating in 1964. He went on to Graceland College the fall of 1964 where he lettered in Varsity Wrestling. He graduated in the spring of 1969 and majored with a B.A. in Business.

He was a baptized into the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints at the age of 8 years old and was called into the priesthood while in college. He remained faithful in this restoration movement until his death. He has always been a strong advocate for the Lord and has done anything the Lord has asked him to do without fear.

David was preceded in death by his father, Albert Donald Swayne, mother, Rosemary Clisby, brother, Richard Kent Swayne, and sister, Rosemary Lorene Swayne Storaasli. He is survived by his wife, Paula Diane Glover Swayne, his children; Douglas Hopkins Swayne, Bradley Kent Swayne, Cara Timell Swayne Frye, and step-children, Camille Gabrielle Levin Seever and Christopher Travis Levin, and nine grandchildren.

Memorial contributions are suggested to the Joint Conference of Restoration Branches Missionary Fund at 1100 W Truman Rd, Independence, MO 64050 or the Dementia Society of America at https://secure.dementiasociety.org in the name of David Swayne.

David Hopkins Swayne, 72, of Independence, Missouri passed away September 27, 2018 at his home after suffering from dementia and other health issues for several years. Memorial services will be held at 4:30 p.m. on Sunday, October 14, 2018 at Independence Central/Gospel Park Church of Jesus Christ, 919 S Delaware St, Independence, MO 64050.

David Hopkins Swayne was born on April 17, 1946 in Seattle, Washington. David went Concorde Elementary school in South Park by Boeing Field, then to Asa Mercer Junior High, moving on to Cleveland High School where he was the Yell King and Class President his senior year, graduating in 1964. He went on to Graceland College the fall of 1964 where he lettered in Varsity Wrestling. He graduated in the spring of 1969 and majored with a B.A. in Business.

He was a baptized into the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints at the age of 8 years old and was called into the priesthood while in college. He remained faithful in this restoration movement until his death. He has always been a strong advocate for the Lord and has done anything the Lord has asked him to do without fear.

David was preceded in death by his father, Albert Donald Swayne, mother, Rosemary Clisby, brother, Richard Kent Swayne, and sister, Rosemary Lorene Swayne Storaasli. He is survived by his wife, Paula Diane Glover Swayne, his children; Douglas Hopkins Swayne, Bradley Kent Swayne, Cara Timell Swayne Frye, and step-children, Camille Gabrielle Levin Seever and Christopher Travis Levin, and nine grandchildren.

Memorial contributions are suggested to the Joint Conference of Restoration Branches Missionary Fund at 1100 W Truman Rd, Independence, MO 64050 or the Dementia Society of America at https://secure.dementiasociety.org in the name of David Swayne.

There are currently no tributes.

Paul John (Big Wally) Wallrof

Birth Date:

1932-07-10

Graduation year:

1949

Deceased Date:

2018-08-28

Obituary: